by Dani Avriel

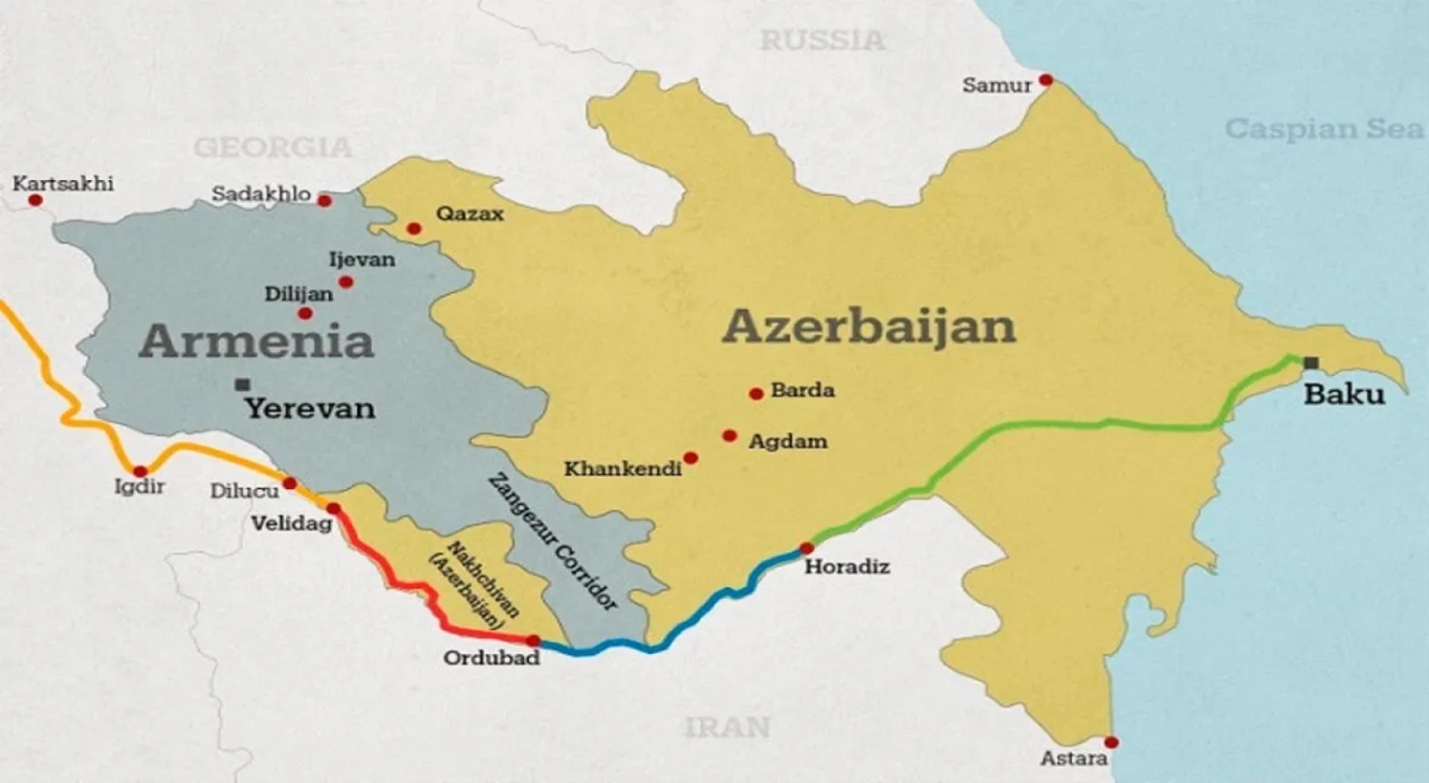

Armenia: from a “promise of marriage” to India to diversification flirting with Pakistan

The peace agreement between Azerbaijan and Armenia, brokered by U.S. President Donald Trump on August 8, 2025, opened not only new opportunities for interaction and regional stabilization but also revealed the emergence of a new configuration of influence. The South Caucasus—traditionally the second-most significant arena of international rivalry after Ukraine—has once again found itself at the intersection of the interests of both regional and extra-regional powers. Many of these actors do not share borders with the region, yet seek to incorporate it into their own geopolitical calculations. Against this backdrop, the traditional centers of power—Russia, Turkey, and Iran—retain influence, though no longer in the former, uncontested format. Increasingly visible, too, is an external line of confrontation previously regarded as peripheral to the Caucasus. A striking example is the rivalry between India and Pakistan, which is now more frequently projected onto the region through infrastructure, logistics, and technology-driven initiatives.

U.S. President Donald Trump, Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev, and Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan, August 8, 2025

In regional politics, India has consistently oriented itself toward Armenia, while Pakistan has aligned with Azerbaijan. Until recently, this very configuration defined the political and military-technical logic of the South Caucasus. As post-conflict stabilization advances, however, this framework has begun to falter, signaling the emergence of a more complex and multilayered balance of power.

A key signal: a diplomatic breakthrough on the margins of the SCO

The first signs of change became evident in late summer 2025. On August 31–September 1, on the sidelines of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) summit, it was announced that Armenia and Pakistan had reached an agreement to establish diplomatic relations. This step outlined new contours of regional dynamics and foreshadowed a revision of the previous foreign policy architecture, in which India, Pakistan, Armenia, and Azerbaijan had been the principal actors.

SCO Summit, 2025

The Armenian–Pakistani rapprochement, however, should not be viewed as an isolated diplomatic episode. Pakistan has long been embedded in a stable axis of influence with China, where political decisions are consistently reinforced by logistics and infrastructure. Unlike India’s approach—focused on routes through the South Caucasus based on the Persian Gulf–Black Sea linkage—the Sino-Pakistani configuration promotes an alternative logistics model: China–South Caucasus–Europe, minimizing dependence on Indian transit decisions.

In this context, the South Caucasus acquires a different significance—not as a peripheral direction, but as an element of a broader system of interconnected corridors. For Armenia, this shift is particularly sensitive. Until recently, Yerevan found itself at a crossroads between the Persian Gulf–Black Sea direction and the Middle Corridor. The latter is increasingly aligned with the underlying logic of the current U.S. initiative known as the “Trump Route” (TRIPP)—a logistics corridor passing through Armenia and forming part of the Middle Corridor. Armenia’s accession to the Middle Corridor marks a cooling toward the alternative “Persian Gulf–Black Sea” project, designed to connect India with Europe via Iran, Armenia, and Georgia. This, in turn, reduces the prospects for Armenia’s alliance-based interaction with India to the level of an ordinary partnership.

The “Trump Route” (TRIPP)

China, unlike Pakistan, has been present in Armenia for quite some time and is not limited to political declarations. Nine seismic monitoring laboratories operate on Armenian territory under the supervision of the Institute of Geophysics of the China Earthquake Administration. Formally launched in 2023 as a scientific cooperation project, this initiative nevertheless provides Beijing with direct access to geological and infrastructure data. This picture is further complemented by China’s regular expressions of readiness to participate in the development of Armenia’s nuclear energy sector—an area with an obvious dual-use, including technological, dimension.

Taken together, these elements fit into the logic of the “Digital Silk Road,” where infrastructure, data, and energy serve as instruments of long-term influence. Whereas the South Caucasus was previously perceived largely as a projection of the Indo-Pakistani rivalry—by analogy with the Kashmir conflict—this framework is now losing relevance. What is coming to the fore instead is the far more rigid and systemic competition between India and China, within which Pakistan acts as a connective and operational element. The restoration of its diplomatic contacts with Armenia merely formalizes this shift.

A “sisterly calculation” in Indo-Azerbaijani relations

Throughout the period when Armenia was effectively promising to bind itself in “marital ties” to the Indian route, New Delhi actively employed various instruments of pressure against Azerbaijan. Prior to the SCO summit, India constrained Baku’s economic and diplomatic opportunities. In the first half of 2025, tourist flows from India to Azerbaijan fell by nearly 9 percent—from 117,000 to 105,000 visitors. This was partly explained by Azerbaijan’s support for Pakistan during a brief Indo-Pakistani escalation. Several Indian travel companies canceled trips to Azerbaijan, vividly illustrating how political confrontation spilled over into the humanitarian and economic spheres.

Pressure was also exerted on international platforms. At the same SCO summit where Armenia formalized diplomatic contacts with Pakistan, India blocked Azerbaijan’s application for full membership in the organization. Azerbaijani diplomats emphasized that this move came amid decisions taken by Islamabad in coordination with Baku.

The blocking tactic had been used before. In 2024, at COP29 in Baku, Delhi impeded the adoption of a USD 300 billion climate finance package for developing countries—an episode that coincided with Armenia’s active anti-Azerbaijani campaign. This case demonstrated the depth of political involvement in the Indo-Armenian alignment, yet it failed to deliver the desired outcome.

The calculation is complete

Apparently, Yerevan concluded that the resource of exploiting the “Aryan sister” for anti-Azerbaijani purposes had been exhausted, and that rapprochement with Pakistan no longer carried the risk of forfeiting potential dividends along the Indian vector. Viewed through this lens, Armenia’s decision to initiate an institutionalized dialogue with Pakistan became a marker of the end of its previous foreign policy cycle. This is no longer about symbolic contacts: the parties are discussing the details of opening a Pakistani embassy in Yerevan, thereby cementing Armenia’s turn toward the Sino-Pakistani axis and elevating this vector from a situational maneuver to a long-term strategic bet.

Indian Akash air defense system supplied to Armenia

During the Karabakh war and in the years that followed, Armenia consistently extracted the maximum possible benefit from its interaction with New Delhi—both militarily and diplomatically. Arms supplies, personnel training, and political support were viewed in Yerevan as key compensators for the lost balance of power. Even in the post-war period, up until the signing of the peace agreement in August 2025, this cooperation retained practical intensity: according to several estimates, Indian weapons accounted for as much as 43 percent of Armenia’s military imports in 2022–2024.

Formally, the Indian line remains in place. India’s Ministry of External Affairs spokesperson Randhir Jaiswal states that New Delhi “stands with Armenia” and continues to develop cooperation, particularly in the defense sphere.

However, with the onset of the peace phase with Azerbaijan and Armenia’s integration into alternative strategic international initiatives, India’s political value for Yerevan has begun to decline rapidly. New Delhi—anchored in a logic of confrontation and containment—has proven less in demand in a new reality where logistics, infrastructure, and integration into alternative axes of influence come to the fore. Under these conditions, Yerevan has shifted its emphasis toward the Chinese direction, supplementing it with the Pakistani factor—a move that reinforces the anti-Indian orientation of Armenian policy, even if it is not articulated in public statements.

In effect, Armenia has closed the Indian chapter, having utilized its resources during a critical period, and has moved on to shaping a broader configuration of external pillars. How viable the maneuvering space created by the Sino-Pakistani axis will prove remains an open question. Attempting to balance between competing centers of power—while intensifying the anti-Indian vector without clear guarantees from new partners—may result not in expanded opportunities, but in strategic uncertainty. In a context where previous resources have already been exhausted and new axes of influence have yet to be tested in practice, the price of such a pivot risks exceeding the expected dividends.